Chris Giles in The Financial Times

Central bankers usurped the titans of Wall Street as the masters of the universe almost a decade ago. They rescued the global economy from the financial crisis, flooding the world with cheap money. They used their powers effectively to get banks lending again. Their actions raised asset prices, keeping business and consumer confidence up. Financial markets and populations hang on their words. But never have they been so vulnerable.

As they gather in Washington for the annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund, there is a crisis of confidence in central banking. Their economic models are failing and there are doubts whether they understand the effects of interest rates and other monetary policies on the economy.

In short, the new masters of the universe might not understand what makes a modern economy tick and their well-intentioned actions could prove harmful.

While there have long been critics of the power of central bankers on the left and the right, such profound doubts have never been so present within their narrow world. In the words of billionaire investor Warren Buffett, they risk being the next ones to be found swimming naked when the tide goes out.

The ability of central banks to resolve these questions does not just affect growth rates, but is fundamental to the health of the democracies of advanced economies, many of which have been assailed by populist uprisings.

“If we can’t get inflation back up [trouble lies ahead]. We can’t have political stability without wage growth,” says Adam Posen, head of the Peterson Institute and formerly a central banker at the Bank of England.

The root of the current insecurity around monetary policy is that in advanced economies — from Japan to the US — inflation is not behaving in the way economic models predicted.

Deflation failed to materialise in the depths of the great recession of 2008-09 and now that the global economy is enjoying its broadest and strongest upswing since 2010, inflationary pressures are largely absent. Even as the unemployment rate across advanced economies has fallen from almost 9 per cent in 2009 to less than 6 per cent today, IMF figures this week show wage growth has been stuck hovering around annual increases of 2 per cent. The normal relationships in the labour market have broken down.

Amid this forecasting nightmare, some frank talk is breaking out. Janet Yellen, chair of the US Federal Reserve and the world’s most important central banker, has been the most direct. “Our framework for understanding inflation dynamics could be mis-specified in some fundamental way,” she said last month. Her sentiments are spreading.

For Mark Carney, governor of the BoE, global considerations “have made it more difficult for central banks to set policy in order to achieve their objectives”. Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, is keeping the faith for now, but observes, “the ongoing economic expansion . . . has yet to translate sufficiently into stronger inflation dynamics”.

Claudio Borio, chief economist of the Bank for International Settlements, which provides banking services to the world’s central banks, says: “If one is completely honest, it is hard to avoid the question: how much do we really know about the inflation process?”

The details of macroeconomic models are fiendishly complicated, but at their heart is a relationship — called the Phillips curve — between the economic cycle and inflation. The cycle can be measured by unemployment, the rate of growth or other variables, and the model predicts that if the economy is running hot — if unemployment falls below a long-run sustainable level or if growth is persistently faster than its speed limit — inflation will rise.

The models are augmented by a concept of inflation expectations, which keep inflation closer to a central bank’s target — usually 2 per cent — if the public trusts that central bankers will do whatever it takes to return inflation to that level after any temporary deviation. The holy grail for central bankers is to claim credibly that they have “anchored inflation expectations” at the target level.

In the model, the most important factors that explain price movements are therefore the degree to which the economy has room to grow without inflation, termed “slack” or “the output gap”, and the public’s inflation expectations.

The role of central banks in the model is to set the short-term interest rate. If a central bank sets its official interest rates low, people and companies will be encouraged to borrow more to spend and invest and discouraged from saving, boosting the economy in the short term. Higher interest rates cool demand.

The first fundamental problem with the model is, as Mr Borio says, “the link between measures of domestic slack and inflation has proved rather weak and elusive for at least a couple of decades”.

While Japan’s unemployment rate is now back down to the levels of the 1970s and 1980s boom, leaving little slack, inflation is barely above zero. In Britain, unemployment has almost halved since 2010, but wage growth has stuck resolutely at 2 per cent a year.

But many economists and central bankers are wedded to the underlying theory, which is about 30 years old, and seek to tweak it to explain recent events rather than ditch it in favour of less orthodox ideas. Such nips and tucks are occurring all over the world, although the explanations differ.

Ms Yellen has highlighted measurement issues in inflation and “idiosyncratic shifts in the prices of some items, such as the large decline in telecommunication service prices seen earlier in the year”. Similarly, the ECB is fond of a new definition — “super core inflation”, which strips out more items from the index and shows the bank performing better against its target than the headline measure. But few central bankers are happy with meeting targets only once they have moved the goalposts.

A second explanation is that the level of unemployment that is consistent with stable inflation has fallen. In 2013, the BoE thought the UK economy could not withstand unemployment falling below 7 per cent before wages and inflation would pick up. It now thinks that rate is 4.5 per cent. On this reasoning, inflation has been low because there was more slack in the economy than they had thought.

The problem with such explanations, as Daniel Tarullo, a Fed governor for eight years until April, notes, is that if central bankers keep changing their notion of sustainable unemployment levels “sound estimation and judgment are sometimes hard to differentiate from guesswork in attempting to see through transitory developments”.

A third explanation is that central bankers have been so successful in anchoring inflation expectations, companies do not seek to raise prices any faster and workers do not ask for wage rises even when jobs are plentiful.

Mr Draghi recently urged union pay bargainers to stop looking backward at inflation rates of the past when they negotiate wages, in a move that used to be unthinkable for a central banker. The problem with this explanation is both the self-serving reasoning and the fact that inflation expectations cannot be measured.

“Over my time at the Fed, I came to worry that inflation expectations are bearing an awful lot of weight in monetary policy these days, considering the range and depth of unanswered questions about them,” says Mr Tarullo.

The Bank of Japan, meanwhile, frets that companies are cutting employees’ hours and raising productivity rather than paying more, which is hampering its ability to push up inflation despite extremely low unemployment.

If it was not bad enough that the link between the economic cycle and inflation has broken down, the second fundamental problem in central banking is that estimates of the neutral rate of interest — seen as the long-term rate of interest that balances people’s desire to save and invest with their desire to borrow and spend — appear to have fallen persistently across the world.

The Fed’s central estimates of the real neutral interest rate has declined by nearly two-thirds in five years, from 2 per cent to 0.75 per cent. But the figures are again little more than guesswork. As Ms Yellen said, “[the neutral rate’s] value at any point in time cannot be estimated or projected with much precision”.

Whether it is because ageing populations want to save more or because of a global “savings glut”, as former Fed chair Ben Bernanke said, low rates no longer have the same impact, limiting the effectiveness of the medicine central banks want to administer.

Regardless of the terminology, the two problems combined suggest central bankers cannot easily determine whether their economies need stimulus or cooling and do not know whether their monetary tools are helping them do their job. And there is increasing concern, even expressed by Ms Yellen, that the underlying theoretical model might simply be rotten to the core and attempts to tweak it are futile.

“Essentially you are setting policy on things you don’t know and can’t measure and then reasoning after the fact,” says Mr Tarullo. His core argument is that central banks maintain an absolute faith in the model with absolutely no evidence to support it.

At a conference last month to celebrate the BoE’s 20 years of independence, Christina Romer, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, urged central bankers to have a more open mind.

New research is needed to question whether current thinking is deficient, she said, “and if such research suggests our ideas explaining how the economy works are wrong or need to change, then central bankers need to embrace those ideas”.

The most aggressive critic of the consensus is Mr Borio of the BIS. He accuses central bankers of misunderstanding the drivers of inflation and their effects on the economy. His argument is that global forces of trade integration and technology are more convincing than concepts of domestic slack in explaining the absence of pricing power among companies and employees.

He asks: “Is it reasonable to believe that the inflation process should have remained immune to the entry into the global economy of the former Soviet bloc and China and to the opening up of other emerging market economies?”

His concern is that by keeping interest rates low, central bankers have no effect on inflation or the economy other than to increase the level of debt. The result is that it will be harder “to raise interest rates without causing economic damage, owing to the large debts and distortions in the real economy that the financial cycle creates”.

It is not a popular view, but it is no longer dismissed out of hand. Ms Yellen justified her stance on continuing to raise interest rates gradually in the face of persistently low inflation by appealing to concerns about debt.

“Persistently easy monetary policy might also eventually lead to increased leverage and other developments, with adverse implications for financial stability,” she said.

With central bankers credited for keeping the economic show on the road over the past decade, it will come as a shock to many to hear how little confidence they have in their models, their policies and their tools.

One question posed by Richard Barwell, a senior economist at BNP Paribas, is whether they should let on about how little they know. “It’s rather like Daddy is driving the car down a hill, turning round to the family and saying, ‘I’m not sure the brakes work, but trust me anyway’,” he says.

For now, the public still trust the women and men who work in the marbled halls of central banks around the world. But that confidence is fragile. Central bankers might have been the masters of the universe of the past decade, but they know well what happened to the previous holders of that title.

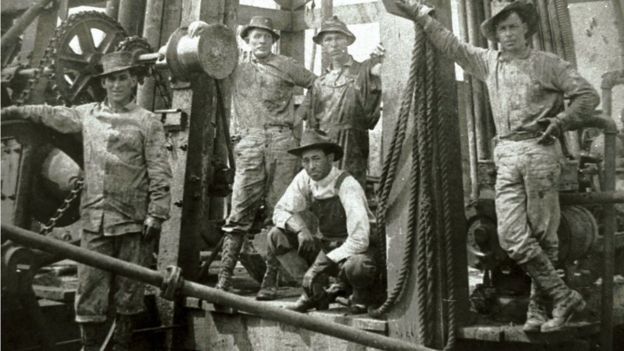

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage caption A drilling crew poses for a photograph at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas where the first Texas oil gusher was discovered in 1901.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage caption A drilling crew poses for a photograph at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas where the first Texas oil gusher was discovered in 1901. Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage captionServers for data storage in Hafnarfjordur, Iceland, which is trying to make a name for itself in the business of data centres - warehouses that consume enormous amounts of energy to store the information of 3.2 billion internet users.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage captionServers for data storage in Hafnarfjordur, Iceland, which is trying to make a name for itself in the business of data centres - warehouses that consume enormous amounts of energy to store the information of 3.2 billion internet users.