By Thomas Frank in Harper's Magazine in 2016

All politicians love to complain about the press. They complain for good reasons and bad. They cry over frivolous slights and legitimate inquiries alike. They moan about bias. They talk to friendlies only. They manipulate reporters and squirm their way out of questions. And this all makes perfect sense, because politicians and the press are, or used to be, natural enemies.

Conservative politicians have built their hostility toward the press into a full-blown theory of liberal media bias, a pseudosociology that is today the obsessive pursuit of certain nonprofit foundations, the subject matter of an annual crop of books, and the beating heart of a successful cable-news network. Donald Trump, the current leader of the right’s war against the media, hates this traditional foe so much that he banned a number of news outlets from attending his campaign events and has proposed measures to encourage more libel lawsuits. He does this even though he owes his prominence almost entirely to his career as a TV celebrity and to the news media’s morbid fascination with his glowering mug.

His Democratic opponent hates the press, too. Hillary Clinton may not have a general theory of right-wing media bias to fall back on, but she knows that she has been the subject of lurid journalistic speculation for decades. Back in the Nineties, she watched her husband’s presidency drown in an endless series of petty scandals and petty fake scandals, many of them featuring her as a kind of diabolical villainess, and to this day, she stays well clear of press conferences. She does this even though it was the passionate enthusiasm of the punditry that made her husband a real contender in 1992—and even though she has stayed close to several commentators who did exemplary pro-Clinton journalism back in those days.

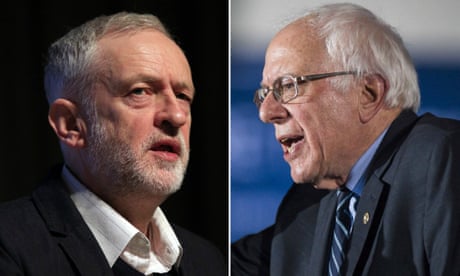

My project in the pages that follow is to review the media’s attitude toward yet a third politician, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who ran for the Democratic presidential nomination earlier this year. By examining this recent history, much of it already forgotten, I hope to rescue a number of worthwhile facts about the press’s attitude toward Sanders. Just as crucially, however, I intend to raise some larger questions about the politics of the media in this time of difficulty and transition (or, depending on your panic threshold, industry-wide apocalypse) for newspapers.

To refresh your memory, the Vermont senator is an independent who likes to call himself a “democratic socialist.” He ran for the nomination on a platform of New Deal–style economic interventions such as single-payer health insurance, a regulatory war on big banks, and free tuition at public universities. Sanders was well to the left of where modern Democratic presidential candidates ordinarily stand, and in most elections, he would have been dismissed as a marginal figure, more petrified wood than presidential timber. But 2016 was different. It was a volcanic year, with the middle class erupting over a recovery that didn’t include them and the obvious indifference of Washington, D.C., toward the economic suffering in vast reaches of the country.

For once, a politician like Sanders seemed to have a chance with the public. He won a stunning victory over Hillary Clinton in the New Hampshire primary, and despite his advanced age and avuncular finger-wagging, he was wildly popular among young voters. Eventually he was flattened by the Clinton juggernaut, of course, but Sanders managed to stay competitive almost all the way to the California primary in June.

His chances with the prestige press were considerably more limited. Before we go into details here, let me confess: I was a Sanders voter, and even interviewed him back in 2014, so perhaps I am naturally inclined to find fault in others’ reporting on his candidacy. Perhaps it was the very particular media diet I was on in early 2016, which consisted of daily megadoses of the New York Times and the Washington Post and almost nothing else. Even so, I have never before seen the press take sides like they did this year, openly and even gleefully bad-mouthing candidates who did not meet with their approval.

This shocked me when I first noticed it. It felt like the news stories went out of their way to mock Sanders or to twist his words, while the op-ed pages, which of course don’t pretend to be balanced, seemed to be of one voice in denouncing my candidate. A New York Times article greeted the Sanders campaign in December by announcing that the public had moved away from his signature issue of the crumbling middle class. “Americans are more anxious about terrorism than income inequality,” the paper declared—nice try, liberal, and thanks for playing. In March, the Times was caught making a number of post-publication tweaks to a news story about the senator, changing what had been a sunny tale of his legislative victories into a darker account of his outrageous proposals. When Sanders was finally defeated in June, the same paper waved him goodbye with a bedtime-for-Grandpa headline, hillary clinton made history, but bernie sanders stubbornly ignored it.

I propose that we look into this matter methodically, and that we do so by examining Sanders-related opinion columns in a single publication: the Washington Post, the conscience of the nation’s political class and one of America’s few remaining first-rate news organizations. I admire the Post’s investigative and beat reporting. What I will focus on here, however, are pieces published between January and May 2016 on the paper’s editorial and op-ed pages, as well as on its many blogs. Now, editorials and blog posts are obviously not the same thing as news stories: punditry is my subject here, and its practitioners have never aimed to be nonpartisan. They do not, therefore, show media bias in the traditional sense. But maybe the traditional definition needs to be updated. We live in an era of reflexive opinionating and quasi opinionating, and we derive much of our information about the world from websites that have themselves blurred the distinction between reporting and commentary, or obliterated it completely. For many of us, this ungainly hybrid is the news. What matters, in any case, is that all the pieces I review here, whether they appeared in pixels or in print, bear the imprimatur of the Washington Post, the publication that defines the limits of the permissible in the capital city.

Why should anyone care today that the pundits were unkind to Bernie Sanders? The primaries are long over. Even the senator’s most die-hard fans suspect that he is unlikely to run for the presidency again. His campaign is, as we like to say, history. Still, I think that what befell the Vermont senator at the hands of the Post should be of interest to all of us. For starters, what I describe here represents a challenge to the standard theory of liberal bias. Sanders was, obviously, well to the left of Hillary Clinton, and yet that did not protect him from the scorn of the Post—a paper that media-hating conservatives regard as a sort of liberal death squad. Nor was Sanders undone by some seedy journalistic obsession with scandal or pseudoscandal. On the contrary, his record seemed remarkably free of public falsehoods, security-compromising email screwups, suspiciously large paychecks for pedestrian speeches, escapades with a comely staffer, or any of that stuff.

An alternative hypothesis is required for what happened to Sanders, and I want to propose one that takes into account who the media are in these rapidly changing times. As we shall see, for the sort of people who write and edit the opinion pages of the Post,there was something deeply threatening about Sanders and his political views. He seems to have represented something horrifying, something that could not be spoken of directly but that clearly needed to be suppressed.

Who are those people? Let us think of them in the following way. The Washington Post, with its constant calls for civility, with its seemingly genetic predisposition for bipartisanship and consensus, is more than the paper of record for the capital—it is the house organ of a meritocratic elite, which views the federal city as the arena of its professional practice. Many of its leading personalities hail from a fairly exalted socioeconomic background (as is the case at most important American dailies). Its pundits are not workaday chroniclers of high-school football games or city-council meetings. They are professionals in the full sense of the word, well educated and well connected, often flaunting insider credentials of one sort or another. They are, of course, a comfortable bunch. And when they look around at the comfortable, well-educated folks who work in government, academia, Wall Street, medicine, and Silicon Valley, they see their peers.11 The professionalization of journalism is a well-known historical narrative. James Fallows, in Breaking the News (1996), describes how journalism went from being “a high working-class activity” to an occupation for “college boys” in the mid-1960s. The Washington Post’s role in this story, as a compulsive employer of Ivy League graduates, is also well known. Indeed, the concentration of obnoxious Ivy Leaguers at the Post was once so great, Fallows writes, that editor Leonard Downie (who went to Ohio State) was known among his colleagues as “Land-Grant Len.” At present, five of the eight members of the Post’s editorial board are graduates of Ivy League universities.

Now, consider the recent history of the Democratic Party. Beginning in the 1970s, it has increasingly become an organ of this same class. Affluent white-collar professionals are today the voting bloc that Democrats represent most faithfully, and they are the people whom Democrats see as the rightful winners in our economic order. Hillary Clinton, with her fantastic résumé and her life of striving and her much-commented-on qualifications, represents the aspirations of this class almost perfectly. An accomplished lawyer, she is also in with the foreign-policy in crowd; she has the respect of leading economists; she is a familiar face to sophisticated financiers. She knows how things work in the capital. To Washington Democrats, and possibly to many Republicans, she is not just a candidate but a colleague, the living embodiment of their professional worldview.

In Bernie Sanders and his “political revolution,” on the other hand, I believe these same people saw something kind of horrifying: a throwback to the low-rent Democratic politics of many decades ago. Sanders may refer to himself as a progressive, but to the affluent white-collar class, what he represented was atavism, a regression to a time when demagogues in rumpled jackets pandered to vulgar public prejudices against banks and capitalists and foreign factory owners. Ugh.

Choosing Clinton over Sanders was, I think, a no-brainer for this group. They understand modern economics, they know not to fear Wall Street or free trade. And they addressed themselves to the Sanders campaign by doing what professionals always do: defining the boundaries of legitimacy, by which I mean, defining Sanders out.

After reading through some two hundred Post editorials and op-eds about Sanders, I found a very basic disparity. Of the Post stories that could be said to take an obvious stand, the negative outnumbered the positive roughly five to one.2 (Opinion pieces about Hillary Clinton, by comparison, came much closer to a fifty-fifty split.)

One of the factors making this result so lopsided was the termination, in December, of Harold Meyerson, a social democrat and the only regular Post op-ed personality who might have been expected to support Sanders consistently. Fred Hiatt, who oversees the paper’s editorial page, told Politico that Meyerson “failed to attract readers.” Meyerson offered the magazine an additional explanation for his firing. Hiatt, he said, had blamed his unpopularity on his habit of writing about “unions and Germany”—meaning, presumably, that nation’s status as a manufacturing paradise.2 For research purposes, I used the Nexis electronic search service to find allWashington Post stories mentioning Bernie Sanders and identified as “editorial copy.” Judgments of what constituted “negative” and “positive” were made by me and a Harper’s Magazine intern and were entirely subjective. In arriving at this ratio, I did not count letters to the editor, articles that appeared in other sections of the paper, or blog posts, even though a number of the latter are reviewed in this essay. Throughout, I have used print rather than online headlines (which sometimes differ for identical stories). And finally: I am indebted to Adam Johnson of Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting for his help with this essay.

But the factor that really mattered was that the Post’s pundit platoon just seemed to despise Bernie Sanders. The rolling barrage against him began during the weeks before the Iowa caucuses, when it first dawned on Washington that the Vermonter might have a chance of winning. And so a January 20 editorial headlined level with us, mr. sanders decried his “lack of political realism” and noted with a certain amount of fury that Sanders had no plans for “deficit reduction” or for dealing with Social Security spending—standard Postsignifiers for seriousness. That same day, Catherine Rampell insisted that the repeal of Glass–Steagall “had nothing to do with the 2008 financial crisis,” and that those populists who pined for the old system of bank regulation were just revealing “the depths of their ignorance.”33 In point of fact, several authoritative works on the crisis describe how the multi-step repeal of Glass–Steagall (and the weak regulation that replaced it) set the stage for the meltdown. Nevertheless, dismissing the significance of the Glass–Steagall repeal was a frequent talking point for anti-Sanders pundits, possibly because (a) that’s what Hillary Clinton was saying, and (b) it showed their solidarity with the many experts and politicians who had participated in the repeal of Glass–Steagall, and (c) Glass–Steagall was killed off by the very sort of universal, bipartisan consensus that the Post frequently claims to be the model of correct policymaking.

The next morning, Charles Lane piled on with an essay ridiculing Sanders’s idea that there was a “billionaire class” that supported conservative causes. Many billionaires, Lane pointed out, are actually pretty liberal on social issues. “Reviewing this history,” he harrumphed, “you could almost get the impression billionaires have done more to advance progressive causes than Bernie Sanders has.”

On January 27, with the Iowa caucuses just days away, Dana Milbank nailed it with a headline: nominating sanders would be insane. After promising that he adored the Vermont senator, he cautioned his readers that “socialists don’t win national elections in the United States.” The next day, the paper’s editorial board chimed in with a campaign full of fiction, in which they branded Sanders as a kind of flimflam artist: “Mr. Sanders is not a brave truth-teller. He is a politician selling his own brand of fiction to a slice of the country that eagerly wants to buy it.”

Stung by the Post’s trolling, Bernie Sanders fired back—which in turn allowed no fewer than three of the paper’s writers to report on the conflict between the candidate and their employer as a bona fide news item. Sensing weakness, the editorial board came back the next morning with yet another kidney punch, this one headlined the real problem with mr. sanders. By now, you can guess what that problem was: his ideas weren’t practical, and besides, he still had “no plausible plan for plugging looming deficits as the population ages.”

Actually, that was only one of two editorials to appear on January 29 berating Sanders. The other sideswiped the senator in the course of settling a question of history, evidently one of the paper’s regular duties. After the previous week’s lesson about Glass–Steagall, the editorial board now instructed politicians to stop reviling tarp—i.e., the Wall Street bailouts with which the Bush and Obama Administrations tried to halt the financial crisis. The bailouts had been controversial, the paper acknowledged, but they were also bipartisan, and opposing or questioning them in the Sanders manner was hereby declared anathema. After all, the editorial board intoned:

Contrary to much rhetoric, Wall Street banks and bankers still took losses and suffered upheaval, despite the bailout—but TARP helped limit the collateral damage that Main Street suffered from all of that. If not for the ingenuity of the executive branch officials who designed and carried out the program, and the responsibility of the legislators who approved it, the United States would be in much worse shape economically.

As a brief history of the financial crisis and the bailout, this is absurd. It is true that bailing out Wall Street was probably better than doing absolutely nothing, but saying this ignores the many other options that were available to public officials had they shown any real ingenuity in holding institutions accountable. All the Wall Street banks that existed at the time of TARP are flourishing to this day, since the government moved heaven and earth to spare them the consequences of the toxic securities they had issued and the lousy mortgage bets they made. The big banks were “made whole,” as the saying goes. Main Street banks, meanwhile, died off by the hundreds in 2009 and 2010. And average home owners, of course, got no comparable bailout. Instead, Main Street America saw trillions in household wealth disappear; it entered into a prolonged recession, with towering unemployment, increasing inequality, and other effects that linger to this day. There has never been a TARP for the rest of us.

Charles Krauthammer went into action on January 29, too, cautioning the Democrats that they “would be risking a November electoral disaster of historic dimensions” should they nominate Sanders—cynical advice that seems even more poisonous today, as scandal after scandal engulfs the Democratic candidate that so many Post pundits favored. Ruth Marcus brought the hammer down two days later, marveling at the folly of voters who thought the Vermont senator could achieve any of the things he aimed for. Had they forgotten “Obama’s excruciating experience with congressional Republicans”? The Iowa caucuses came the next day, and Stephen Stromberg was at the keyboard to identify the “three delusions” that supposedly animated the campaigns of Sanders and the Republican Ted Cruz alike. Namely: they had abandoned the “center,” they believed that things were bad in the United States, and they perceived an epidemic of corruption—in Sanders’s case, corruption via billionaires and campaign contributions. Delusions all.

And then, mirabile dictu, the Post ran an op-ed bearing the headline the case for bernie sanders (in iowa). It was not an endorsement of Sanders, of course (“This is not an endorsement of Sanders,” its author wrote), but it did favor the idea of a sustained conversation among Democrats. The people of Iowa “must make sure” that the battle between Clinton and Sanders continued. It was the best the Post could do, I suppose, before reverting to its customary position.

On and on it went, for month after month, a steady drumbeat of denunciation. The paper hit every possible anti-Sanders note, from the driest kind of math-based policy reproach to the lowest sort of nerd-shaming—from his inexcusable failure to embrace taxes on soda pop to his awkward gesticulating during a debate with Hillary Clinton (“an unrelenting hand jive,” wrote Post dance critic Sarah L. Kaufman, “that was missing only an upright bass and a plunky piano”).

The paper’s piling-up of the senator’s faults grew increasingly long and complicated. Soon after Sanders won the New Hampshire primary, the editorial board denounced him and Trump both as “unacceptable leaders” who proposed “simple-sounding” solutions. Sanders used the plutocracy as a “convenient scapegoat.” He was hostile to nuclear power. He didn’t have a specific recipe for breaking up the big banks. He attacked trade deals with “bogus numbers that defy the overwhelming consensus among economists.” This last charge was a particular favorite of Post pundits: David Ignatius and Charles Lane both scolded the candidate for putting prosperity at risk by threatening our trade deals. Meanwhile, Charles Krauthammer grew so despondent over the meager 2016 options that he actually pined for the lost days of the Bill Clinton presidency, when America was tough on crime, when welfare was being reformed, and when free trade was accorded its proper respect.

Ah, but none of this was to imply that Bernie Sanders, flouter of economic consensus, was a friend to the working class. Here too he was written off as a failure. Instead of encouraging the lowly to work hard and get “prepared for the new economy,” moaned Michael Gerson, the senator was merely offering them goodies—free health care and college—in the manner of outmoded “20th century liberalism.” Others took offense at Sanders’s health-care plan because it envisioned something beyond Obamacare, which had been won at such great cost.

This brings us to the question of qualifications, a non-issue that nevertheless caused enormous alarm among the punditry for a good part of April. Columnist after columnist and blogger after blogger offered judgments on how ridiculous, how very unjustified it was for Sanders to suggest Clinton wasn’t qualified for the presidency, and whether or not Clinton hadn’t started the whole thing first by implying Sanders wasn’t qualified, and whether she was right when she did or didn’t make that accusation. Reporters got into the act, too, wringing their hands over the lamentable “tone” of the primary contest and wondering what it portended for November. Maybe you’ve forgotten about this pointless roundelay, but believe me, it happened; acres of trees fell so that every breathless minute of it could be documented.

Then there was Sanders’s supposed tin ear for racial issues. Jonathan Capehart (a blogger, op-ed writer, and member of the paper’s editorial board) described the senator as a candidate with limited appeal among black voters, who had trouble talking “about issues of race outside of the confines of class and poverty” and was certainly no heir to Barack Obama. Sanders was conducting a “magic-wand campaign,” Capehart insisted on another occasion, since his voting-reform proposals would never be carried out. Even the inspiring story of the senator’s salad days in the civil-rights movement turned out to be tainted once Capehart started sleuthing. In February, the columnist examined a famous photograph from a 1962 protest and declared that the person in the picture wasn’t Sanders at all. Even when the photographer who took the image told Capehart that it was indeed Sanders, the Post grandee refused to apologize, fudging the issue with bromides: “This is a story where memory and historical certitude clash.” Clearly Sanders is someone to whom the ordinary courtesies of journalism do not apply.

Extra credit is due to Dana Milbank, one of the paper’s cleverest columnists, who kept varying his angle of attack. In February, he name-checked the Bernie Bros—socialist cyberbullies who were turning comment sections into pens of collectivist terror. In March, Milbank assured readers that Democrats were too “satisfied” to sign up with a rebel like Sanders. In April, he lamented Sanders’s stand on trade on the grounds that it was similar to Trump’s and that it would be hard on poor countries. In May, Milbank said he thought it was just awful the way frustrated Sanders supporters cursed and “threw chairs” at the Nevada Democratic convention—and something close to treachery when Sanders failed to rebuke those supporters afterward.4 “It is no longer accurate to say Sanders is campaigning against Clinton, who has essentially locked up the nomination,” the columnist warned on the occasion of the supposed chair-throwing. “The Vermont socialist is now running against the Democratic Party. And that’s excellent news for one Donald J. Trump.”4 The incident of the tossed chairs was cause for much clucking in Post-land. It was mentioned in an editorial on May 19 and referred to in at least three other stories. The myth of the thrown chairs turned out to be hugely exaggerated, while the D.N.C.’s non-neutrality was later established as fact.

The danger of Trump became an overwhelming fear as primary season drew to a close, and it redoubled the resentment toward Sanders. By complaining about mistreatment from the Democratic apparatus, the senator was supposedly weakening the party before its coming showdown with the billionaire blowhard. This matter, like so many others, found columnists and bloggers and op-ed panjandrums in solemn agreement. Even Eugene Robinson, who had stayed fairly neutral through most of the primary season, piled on in a May 20 piece, blaming Sanders and his noisy horde for “deliberately stoking anger and a sense of grievance—less against Clinton than the party itself,” actions that “could put Trump in the White House.” By then, the paper had buttressed its usual cast of pundits with heavy hitters from outside its own peculiar ecosystem. In something of a journalistic coup, the Post opened its blog pages in April to Jeffrey R. Immelt, the CEO of General Electric, so that he, too, could join in the chorus of denunciation aimed at the senator from Vermont. Comfort the comfortable, I suppose—and while you’re at it, be sure to afflict the afflicted.

It should be noted that there were some important exceptions to what I have described. The paper’s blogs, for instance, published regular pieces by Sanders sympathizers like Katrina vanden Heuvel and the cartoonist Tom Toles. (The blogs also featured the efforts of a few really persistent Clinton haters.) The Sunday Outlook section once featured a pro-Sanders essay by none other than Ralph Nader, a kind of demon figure and clay pigeon for many of the paper’s commentators. But readers of the editorial pages had to wait until May 26 to see a really full-throated essay supporting Sanders’s legislative proposals. Penned by Jeffrey Sachs, the eminent economist and professor at Columbia University, it insisted that virtually all the previous debate on the subject had been irrelevant, because standard economic models did not take into account the sort of large-scale reforms that Sanders was advocating:

It’s been decades since the United States had a progressive economic strategy, and mainstream economists have forgotten what one can deliver. In fact, Sanders’s recipes are supported by overwhelming evidence—notably from countries that already follow the policies he advocates. On health care, growth and income inequality, Sanders wins the policy debate hands down.

It was a striking departure from what nearly every opinionator had been saying for the preceding six months. Too bad it came just eleven days before the Post, following the lead of the Associated Press, declared Hillary Clinton to be the preemptive winner of the Democratic nomination.

What can we learn from reviewing one newspaper’s lopsided editorial treatment of a left-wing presidential candidate?

For one thing, we learn that the Washington Post, that gallant defender of a free press, that bold bringer-down of presidents, has a real problem with some types of political advocacy. Certain ideas, when voiced by certain people, are not merely debatable or incorrect or misguided, in the paper’s view: they are inadmissible. The ideas themselves might seem healthy, they might have a long and distinguished history, they might be commonplace in other lands. Nevertheless, when voiced by the people in question, they become damaging.

We hear a lot these days about the dangers to speech posed by political correctness, about those insane left-wing college students who demand to be shielded from uncomfortable ideas. What I am describing here is something similar, but far more consequential. It is the machinery by which the boundaries of the Washington consensus are enforced.

You will recall how, after the Nevada unpleasantness, Eugene Robinson, who claimed to share Sanders’s philosophy, nonetheless condemned the candidate’s criticism of the Democratic Party’s nominating process as “reckless in the extreme.” Impugning the party, Robinson argued, might empower Donald Trump. Looking back from the vantage point of several months, however, it seems to me that the real recklessness is the idea that certain political questions are off-limits to our candidates—that they must not disparage the party machinery, that they must not “revile” the Wall Street bailouts, and so on. Consider the circumstances in which Post pundits demanded that Sanders refrain from disparaging the Democratic National Committee. Democratic elected officials across the country were virtually unanimous in their support of Hillary Clinton, President Obama was doing nearly everything in his power to secure her nomination, and the D.N.C. itself was more or less openly taking her side. All these players were determined (as we later learned) to make this deeply unpopular woman the nominee, regardless of the consequences. Maybe Sanders didn’t have the story exactly right—nobody did, back then. But still: if ever a situation cried out for critique, for millions of newspaper readers gnashing their teeth, this was it.

Perhaps it is reckless of me to say so. Journalists these days are apparently expected to become soldiers in the political war, and so maybe we must weigh what we write against the possibility that it might in some way help the Republican candidate. As I have already noted: I am a liberal, I vote for Democrats, I don’t want Donald Trump to become president, I am almost certainly going to vote for Hillary Clinton. Maybe I should just turn off my laptop right now.

This is a political way of looking at things, I suppose, but it would be more accurate to say that it is anti-political, that it is actively hostile to political ideas. Consider once again the Post’s baseline philosophy, as the editorial board explained it in two February editorials. In one of them, headlined mr. sanders’ attack on reality, the editors denounced the candidate’s “simplistic” views, and argued that by advocating for better policies in certain areas, he was implicitly criticizing President Obama. What’s the harm in that? you might wonder. The Post unfolded its reasoning:

The system—and by this we mean the constitutional structure of checks and balances—requires policymakers to settle for incremental changes. Mr. Obama has scored several ambitious but incomplete reforms that have made people’s lives better while ideologues on both sides took potshots.

What the Post is saying here is that the American system, by its nature, doesn’t permit a president to achieve anything more than “incremental change.” Obama did the best anyone could under this system—indeed, as the paper pointed out, he had “no other option” than to proceed as he did. Therefore he should be exempt from criticism at the hands of other Democrats.

The board explained its philosophy slightly differently in the other editorial, battle of the extremes. Sanders, like Ted Cruz, was said to harbor the toxic belief that “the road to progress is purity, not compromise.” Again, his great failing was his refusal to acknowledge the indisputable rules of the game. Heed the wisdom of our savviest political journalists:

Progress will be made by politicians who are principled but eager to shape compromises, to acknowledge that they do not have a monopoly on wisdom and to accept incremental change. That is a harder message to sell in primary campaigns, but it is a message far likelier to produce a nominee who can win in November—and govern successfully for the next four years.

To say that this gets reality wrong—that there are many examples of sweeping political achievement in U.S. history, that it was indeed possible for Barack Obama to do more than he did in 2009, that even the most ideological politicians sometimes compromise, or that Bernie Sanders (unlike Ted Cruz) actually works well with his Senate colleagues—is only to begin unpacking the errors here. What matters more, though, is the paper’s curious, unrelenting logic. Since sweeping change is structurally impossible, the Postassures us, no such change should be advocated by political candidates. “No we can’t” turns out be the iron law of American politics, and should therefore become the slogan of every aspiring presidential candidate.

Perhaps you have noticed that the paper’s two great ideas, combined in this way, do not really make sense. Let’s say that it’s true, as the Post asserts, that the American system won’t allow a president to achieve high-flown goals—that such accomplishments are simply off-limits, even to a golden-tongued orator or an LBJ-style political animal. Okay. But what’s wrong with a candidate who talks about those goals? By the paper’s own definition, there’s no chance of them ever becoming law. The only person to be penalized for making such grand, hollow promises will be the politician herself, whose followers will be disappointed with her after she foolishly demands a hundred percent of everything (“purity, not compromise”) and is inevitably defeated by the system. Too bad for her, we will say. That was a really dumb way to play it. But why should we care what happens to her?

Indeed, this logic, applied across the board, would require us to condemn even the most pragmatic leaders. What are we to make, for example, of a politician who says we ought to enact some sort of gun control? Everyone knows that there is virtually no way such a measure will get through Congress, and even if it did, there’s the Supreme Court and the Second Amendment to contend with. How about a politician who goes to China and bravely proclaims that “women’s rights are human rights,” when all the wised-up observers know the Chinese system is organized to ensure that such an ideal will not be realized there anytime soon? And shouldn’t the Post be frothing with vituperation at the lèse-majesté of a candidate who once confronted a respected U.S. senator with the suggestion that politics ought to be the “art of making what appears to be impossible possible”?

The reason the Post pundits embrace these tidy sophistries is simple enough. Knee-jerk incrementalism is, after all, a nifty substitute for actually thinking difficult issues through. Bernie Sanders ran for the presidency by proposing reforms that these prestigious commentators, for whatever reason, found distasteful. Rather than grapple with his ideas, however, they simply blew the whistle and ruled them out of bounds. Plans that were impractical, proposals that would never pass Congress—these things are off the table, and they are staying off.

Clinging to this so-called pragmatism is also professionally self-serving. If “realism” is recognized as the ultimate trump card in American politics, it automatically prioritizes the thoughts and observations of the realism experts—also known as the Washington Post and its brother institutions of insider knowledge and professional policy practicality. Realism is what these organizations deal in; if you want it, you must come to them. Legitimacy is quite literally their property. They dole it out as they see fit.

Think of all the grand ideas that flicker in the background of the Sanders-denouncing stories I have just recounted. There is the admiration for consensus, the worship of pragmatism and bipartisanship, the contempt for populist outcry, the repeated equating of dissent with partisan disloyalty. And think of the specific policy pratfalls: the cheers for TARP, the jeers aimed at bank regulation, the dismissal of single-payer health care as a preposterous dream.

This stuff is not mysterious. We can easily identify the political orientation behind it from one of the very first pages of the Roger Tory Peterson Field Guide to the Ideologies.This is common Seaboard Centrism, its markings of complacency and smugness as distinctive as ever, its habitat the familiar Beltway precincts of comfort and exclusivity. Whether you encounter it during a recession or a bull market, its call is the same: it reassures us that the experts who head up our system of government have everything well under control.

It is, of course, an ideology of the professional class, of sound-minded East Coast strivers, fresh out of Princeton or Harvard, eagerly quoting as “authorities” their peers in the other professions, whether economists at MIT or analysts at Credit Suisse or political scientists at Brookings. Above all, this is an insider’s ideology; a way of thinking that comes from a place of economic security and takes a view of the common people that is distinctly patrician.

Now, here’s the mystery. As a group, journalists aren’t economically secure. The boom years of journalistic professionalization are long over. Newspapers are museum pieces every bit as much as Bernie Sanders’s New Deal policies. The newsroom layoffs never end: in 2014 alone, 3,800 full-time editorial personnel got the axe, and the bloodletting continues, with Gannett announcing in September a plan to cut more than 200 staffers from its New Jersey papers. Book-review editors are so rare a specimen that they may disappear completely, unless somebody starts breeding them in captivity. The same thing goes for the journalists who once covered police departments and city government. At some papers, opinion columnists are expected to have day jobs elsewhere, and copy editors have largely gone the way of the great auk.

In other words, no group knows the story of the dying middle class more intimately than journalists. So why do the people at the very top of this profession identify themselves with the smug, the satisfied, the powerful? Why would a person working in a moribund industry compose a paean to the Wall Street bailouts? Why would someone like Post opinion writer Stephen Stromberg drop megatons of angry repudiation on a certain Vermont senator for his “outrageous negativity about the state of the country”? For the country’s journalists—Stromberg’s colleagues, technically speaking—that state is pretty goddamned negative.

Maybe it’s something about journalism itself. This is a field, after all, that has embraced the forces that are killing it to an almost pathological degree. No institution has a greater appetite for trendy internet thinkers than journalism schools. We are all desperately convincing ourselves that we need to become entrepreneurs, or to get ourselves attuned to the digital future—the future, that is, as it is described for us hardheaded journalists by a cast of transparent bullshit artists. When the TV comedian John Oliver recently did a riff on the tragic decline of newspaper journalism, just about the only group in America that didn’t like it was—that’s right, the Newspaper Association of America, which didn’t think we should be nostalgic about the days when its members were successful. Truly, we are like buffalo nuzzling the rifles of our hunters.

Or maybe the answer is that people at the top of the journalism hierarchy don’t really identify with their plummeting peers. Maybe the pundit corps thinks it will never suffer the same fate as, say, the Tampa Tribune. And maybe they’re right. As I wrote this story, I kept thinking back to Sound and Fury, a book that Eric Alterman published in 1992, when the power of pundits was something new and slightly alarming. Alterman suggested that the rise of the commentariat was dangerous, since it supplanted the judgment of millions with the clubby perspective of a handful of bogus experts. When he wrote that, of course, newspapers were doing great. Today they are dying, and as they gutter out, one might expect the power of this phony aristocracy to diminish as well. Instead, the opposite has happened: as serious journalism dies, Beltway punditry goes from strength to strength.

It was during that era, too, that the old-school Post columnist David Broder gave a speech deploring the rise of journalistic insiders, who were too chummy with the politicians they were supposed to be covering. This was, he suggested, not only professionally questionable. It also bespoke a fundamental misunderstanding of the journalist’s role as gadfly and societal superego:

I can’t for the life of me fathom why any journalists would want to become insiders, when it’s so damn much fun to be outsiders—irreverent, inquisitive, impudent, incorrigibly independent outsiders—thumbing our nose at authority and going our own way.

Yes, it’s fun to be an outsider, but it’s not particularly remunerative. As the rising waters inundate the Fourth Estate, it is increasingly obvious that becoming an insider is the only way to hoist yourself above the deluge. Maybe that is one reason why the Washington Post attracted the fancy of megabillionaire Jeff Bezos, and why the Postseems to be thriving, with a fancy new office building on K Street and a swelling cohort of young bloggers ravening to be the next George Will, the next Sid Blumenthal. It remains, however precariously, the cradle of the punditocracy.

Meanwhile, between journalism’s insiders and outsiders—between the ones who are rising and the ones who are sinking—there is no solidarity at all. Here in the capital city, every pundit and every would-be pundit identifies upward, always upward. We cling to our credentials and our professional-class fantasies, hobnobbing with senators and governors, trading witticisms with friendly Cabinet officials, helping ourselves to the champagne and lobster. Everyone wants to know our opinion, we like to believe, or to celebrate our birthday, or to find out where we went for cocktails after work last night.

Until the day, that is, when you wake up and learn that the tycoon behind your media concern has changed his mind and everyone is laid off and that it was never really about you in the first place. Gone, the private office or award-winning column or cable-news show. The checks start bouncing. The booker at MSNBC stops calling. And suddenly you find that you are a middle-aged maker of paragraphs—of useless things—dumped out into a billionaire’s world that has no need for you, and doesn’t really give a damn about your degree in comparative literature from Brown. You start to think a little differently about universal health care and tuition-free college and Wall Street bailouts. But of course it is too late now. Too late for all of us.