The charismatic former Pakistan captain on wanting to be fast, teaching Wasim and Waqar to bowl, the allrounder wars of the 1980s, ball-tampering, and more

Interview by Sam Collins

July 30, 2010

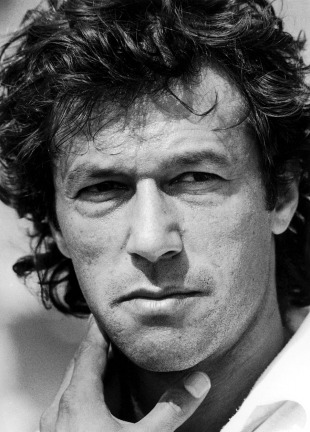

Imran Khan is Pakistan's most famous player and most successful captain. As smooth off the field as he was competitive on it, he made his Test debut as an 18-year-old medium-pacer, transforming himself into a genuinely quick opening bowler and formidable batsman. He led Pakistan to victory in the 1992 World Cup, after which he entered Pakistani politics.

| ||

| Related Links Teams: Pakistan | ||

Was it inevitable that you would become a cricketer?

My two cousins were Test captains. One, Majid Khan, became Test captain while I was playing. One was an Oxford Blue [Javed Burki] and one a Cambridge Blue [Majid]. If you're living up to people who have made it big, you face more pressure than ordinary cricketers. Doors open easier but you're always judged against them. I was always told that I had less talent than them.

You made your Test debut in England aged 18. What happened?

I had always had ambitions as a batsman but I was selected as a fast bowler because Pakistan hardly had any. I'd played very few first-class matches, and while in home conditions my slingy action was effective, in England I was totally at sea. I was dropped after that first Test and my team-mates openly told me I'd never get back into the team. But I'd been determined to be a Test cricketer since I was nine and there was never any chance, no matter how many setbacks I faced, that I would give up.

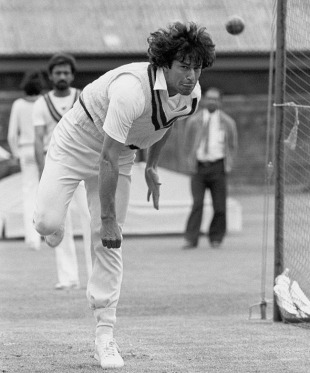

What turned you into a quick bowler?

In 1972, Australia came to England. I watched Dennis Lillee bowl and that's when I decided I wanted to be fast. It was the first time I'd seen a genuine fast bowler. Pakistan didn't have any, and I just loved it. It appealed to my instincts, my aggressive way of playing. I was a medium-pacer then and Worcester would encourage me to bowl that because I had a natural inswinger. But I was never satisfied, so if I ever got hit, I would try and bowl faster. That's how I got this aggressive streak, to seek revenge when a batsman tried to dominate, that made me into a fast bowler. I understood the limitations of how I used to bowl, so I completely restructured my bowling action between the ages of 18 and 25. I spent the winter after I finished at Oxford University [1975-76] in Pakistan, and that was really the turning point, because on those wickets you needed to have air speed. My first-class team [Pakistan International Airlines] encouraged me to bowl fast. In a year I'd gained pace and was genuinely fast.

You came third behind Jeff Thomson and Michael Holding at the famous speed test in Perth in 1978...

We were bowling bouncers and Jeff Thomson was bowling full-tosses, so there was a slight distortion, although he was probably still quicker. Out of eight balls I bowled, seven were quicker than Holding. I wasn't even at my peak - I was quicker in the next two years. In my peak I got nearly 100 wickets in about a year, 40 in a series against India, but I did my shin bone and missed three of my best years as a bowler.

What are your memories of Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket?

It was the highest standard I've played. It was the greatest number of fast bowlers ever concentrated in one place - very high-calibre fast bowling. There were people like Tony Greig, Lawrence Rowe, Roy Fredericks, who were outstanding batsmen, but all three of them sank under the barrage of quick bowlers.

Did captaincy improve you as a player?

The more pressure I took, the stronger I got.

Teams follow captains they believe in. I used to tell them: "Do not be scared of losing, you'll never know how to win." I discovered why I was successful and others who were more talented than me weren't. My whole policy was aggressive: how am I going to win? Most who captained me used to enter a match thinking we should not lose. The result was that team selection became defensive. It's a big difference in strategy and attitude. I took this fear of losing away from them and that's why we used to pull off incredible victories from losing positions. We played superior opposition and did very well. You become fearless and that is a very important component in successful people, organisations, even countries.

| "Waqar was a very strong bowler, not as gifted as Wasim but much stronger physically. Mentally Waqar was very tough. Wasim would give up a little bit when things got down; Waqar would keep coming back" | |||

Did you find it difficult being a bowling captain?

Batting captains never had a clue about bowlers. Most captaincy is done on the field. As a bowler I was far better equipped to deal with that than batting captains. The only batting captain I rated was Ian Chappell. He had a very good cricket mind and could deal with bowlers well. Apart from him, very few were good because they didn't understand bowlers. Because I was a bowling captain, I taught Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis from scratch. They had hardly played any first-class cricket and I would tell them what to do every ball because I had been through the process myself. I would set their fields and I would tell them what to think.

What were the raw ingredients that you saw in Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis?

Wasim was the most talented bowler I have seen apart from Holding. A natural. But he needed the art of taking wickets, fitness and advice, which I gave him. Waqar was a very strong bowler, not as gifted as Wasim, but much stronger physically. Mentally, Waqar was very tough. Wasim would give up a little bit when things got down; Waqar would keep coming back. But Wasim was much more talented.

How do you compare with the three other great allrounders from the 1970s and 80s: Botham, Hadlee, Kapil Dev?

We were all great competitors. I had my duels with all three. Botham was a better batsman than all of them, Hadlee was a better bowler than the others, and Kapil Dev, at one point, had great batting potential but never developed it. It's not easy at that level to keep developing both skills.

Ian Botham peaked very early. I think he was already on the downer at 26 or 27 because he had become very big. He started off as an allrounder of more promise than all of us because he had a great side-on bowling action and outswing. But by his late 20s his bowling was no longer effective. And batting-wise, the reason I don't think he fulfilled his potential is his performance against West Indies. I judge batsmen on their performance against the big boys and in critical situations. In that sense, Botham's performance against West Indies was just appalling - averaging about 14 with the bat and around 40 with the ball [in fact, 21 and 35].

Your bowling average was 21 against West Indies, the dominant team of the era. Did you raise your game against them?

The tougher the competition, the better it got out of me. Sometimes I used to lose motivation against the smaller teams. The lure of beating West Indies in the West Indies was the main reason I came out of retirement [in 1988]. We drew 1-1 but with neutral umpires we would have won 2-0 and I would have retired then because it was my ambition to beat the ultimate team in world cricket. I'm the only captain that never lost to West Indies in three series, all drawn.

They tested you completely. It demanded the greatest concentration, guts and a proper technique to face them. The batting was great too. Viv Richards was head and shoulders above everyone else. A genius. It was his reflexes, his timing, lightning footwork and his attitude. He was very courageous - a batsman who would take on challenges. His statistical record does not reflect his ability or the number of match-winning innings he played. He used to get bored, whereas other batsmen would bat for their averages.

What are your memories of the 1992 World Cup?

Great euphoria. I handpicked that young team and for them to win the World Cup from that impossible situation was a source of such happiness to the Pakistanis. I was so proud of that team. When I retired, I left the best Pakistan team in its history. I was very disappointed that it never achieved its potential. Match-fixing allegations dogged them.

| ||

| | ||

Do you regret admitting to using a bottle top during the 1981 county season?

I regret that it distorted the whole discussion on ball-tampering; it took it to another level. I was trying to explain that ball-tampering had always been part of cricket. It was only when you crossed a certain limit that it became cheating. He [journalist Ivo Tennant] asked me point blank and I said, "Yes". I'd played a match at Sussex against Hampshire. It was a dead wicket, petering towards a draw. We had drinks and there was a bottle top. I scratched the ball trying to get resistance on the other side. I said: "That is cheating, you've crossed the line." I was illustrating the point. Then other people jumped in, people trying to settle scores, people taking money from tabloids to say: "I saw Imran ball-tampering". They were such liars and they made money. In that sense, I regretted it.

There must have been times when the pressure got to you, leading Pakistan for 10 years?

Cricket is the only captaincy in sport where you face pressure. In Pakistan the pressure is more than in other places because when the team loses, the captain's head comes on the chopping block, otherwise the board is removed. There were about 17 changes in the 10-12 years after I left. When I came in, there was a players' revolt against the captain and I was the compromise. In my 10 years I never had a problem. I had the complete respect of the team.

How did cricket prepare you for politics?

Politics is cut-throat. I find myself far better equipped than my colleagues because I learnt to compete and take knocks from sport. There is no better preparation for politics. It is the ultimate in character-building. Being a political leader is like being a cricket captain. You walk out to a stadium full of people, all responsibility on you, and if you can learn to take that responsibility, it equips you to do anything in life.